Beyond the Botanical is Presented by Kiki Frayard

Mare Martin on Drawing, Meditation, and the Intelligence of Nature

Hilliard Presents Studio Sessions

In this extended interview, artist Mare Martin reflects on a lifetime of looking closely—at plants, at matter, and at the quiet intelligence of the natural world.

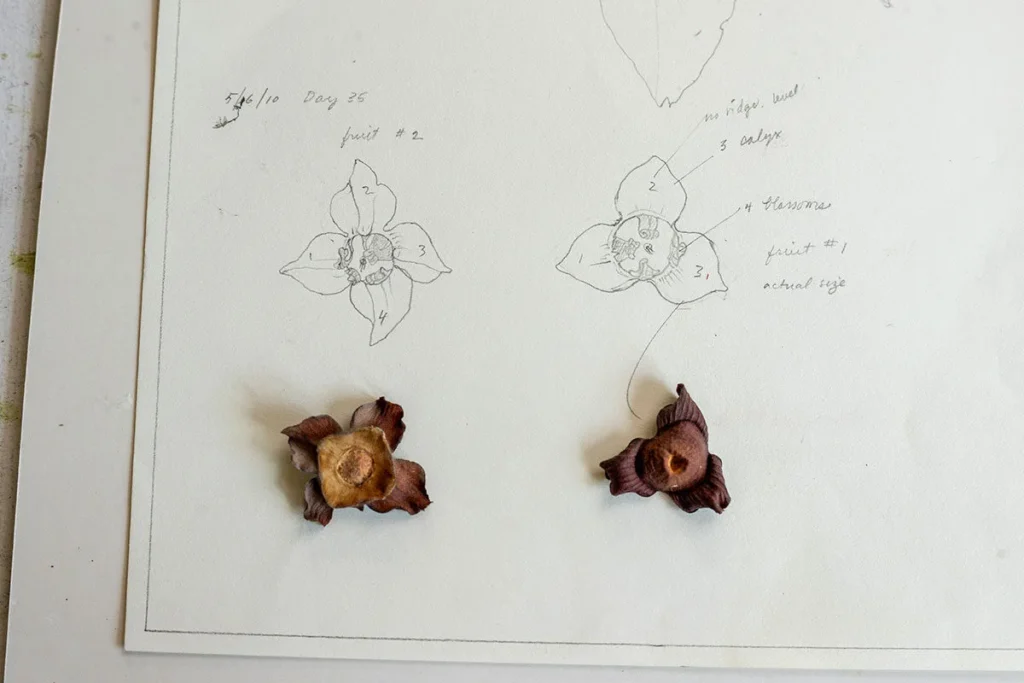

On a summer morning in Opelousas, Louisiana, surrounded by her garden and the quiet hum of nature, artist Mare Martin sits down to talk to the Hilliard Art Museum about art, meditation, and spirit. Her drawings and paintings—delicate studies of plants, leaves, and organic forms in transition—emerge from deep observation and a belief in what she calls “nature intelligence.” Martin’s work is featured in Beyond the Botanical, on view through February 14, 2026, at the Hilliard Art Museum. The exhibition explores the ephemeral and intimate cycles of nature.

In this conversation, she talks about her process, her upbringing on a farm, and the collaboration between the artist and the natural world.

A Life Rooted in Nature

Can you start by introducing yourself and describing what you do?

My name is Mare Martin. I’m an artist, a gardener, and a cook. I make art to share my connection with nature.

I live and work here in my studio in Opelousas, Louisiana. This is where I paint, draw, and think. It’s a small space, but it’s full of everything I need. It’s very private. Very quiet. And nature is all around me. I find it very conducive to working.

When I look out the window to my garden, I feel safe, I feel secure, I feel like my life is where it should be at this moment.

What are the natural elements that draw your attention most?

Anything that’s a plant, plant-related, or nature-related. It might be stones that I have around the plants. My garden is full of diversity. Plants in different stages of growth are always offering something new.

I read once that you must make everything interesting. When I draw, I’ll even write those words—make everything interesting—on the paper. That reminds me. And what that means is that you don’t just draw the flower, you draw the stem. You pay attention to every single thing.

Meditation Through Drawing

It seems like it is a kind of perspective you have, to leave yourself open to finding things interesting.

It is. It’s about focus, too. And it becomes a form of meditation. When I’m drawing a plant, I’m completely present. You can’t drift; you’re there with the pencil, the paper, and the plant. I sometimes sit for forty minutes or more without moving. It’s a meditation I didn’t know I was practicing until I realized how still I’d become. And it really is a wonderful feeling to realize that.

Is there a spiritual aspect to it?

Yes, it’s all spiritual, everything. What I am speaking about is experiential. I believe that what we see—the form of the plant—is also spiritual. Its form is its essence. And there is what I call a natural intelligence that is around the plant, controlling its growth and form. I’m not communicating with the plant itself; that’s not possible. I’m connecting with that intelligence that surrounds the plant and is present in nature. It’s that behind-the-scenes intelligence that I want to honor, to understand, and to propagate.

It took a long time for me to realize it. The intimacy of drawing the plant got me to that space. There was a huge realization that I was more like a collaborator.

You mentioned the word “collaboration.” Can you say more about that?

It took years of drawing to realize that I wasn’t just observing. I was collaborating. Before that, I painted landscapes and general scenes. But when I began to draw individual plants over and over again, in different seasons and different stages, it brought me a unique understanding. It’s a collaboration, which means my ego as an artist has to step aside. I feel more, and then the work is more pure, closer to the truth.

The awesomeness of nature feeds the soul. The soul is enlarged and expanded when you’re in nature. But when you purposefully go out and look for it like you would do with drawings, then you find that zone of collaboration. The action that just comes, and you know it; that is what intuition is. That’s the magic. That’s the collaboration.

The Role of Intuition

You’ve spoken about intuition as essential to your process. Can you tell me more about that?

Well, you know, you can’t purposely capture essence. It comes from intuition. When you have intuition, it means you are getting the full message from the actual thing itself, or from somewhere else. But it’s not you, it’s not coming from you, and that’s pure.

It could be a painting, it could be a watercolor, it could be a print. It’s the same feeling. Although I am the person who translates the pencil to the painting, intuition is what moves into the painting, that special thing that comes from outside of yourself.

And there are ways to get to that place. You can ask for it, or you can just be, waiting for it to come.

Sometimes it comes by accident. But if you keep on using all the accidents that come to you, that intuitive impulse, it’s spiritual. Sometimes I’ll ruin the whole piece because I don’t listen! I have to be conscious of those moments.

That’s part of the collaboration—the willingness to listen.

Have you had to train yourself to have that openness?

Yeah. I had to train. It might come naturally to people who have that propensity for it, but for me, it was through painting. Learning to paint. You must learn the ropes of whatever you do. You learn composition and think about what paint you use and the colors. But in between those things, that’s when the intuition sneaks in and you learn to be aware of it. It can be hard to stay focused when working. But it comes more often now. Now all I have to do is continue to be open and I receive the magic. I’m really pleased that I’ve found a little bit of that.

Goethe and the Metamorphosis of Plants

You’ve cited Goethe’s Metamorphosis of Plants as an influence. How did he influence you?

Yes, Goethe was the turning point, the person who started all this. He’s a German poet, philosopher. Even though he wasn’t a scientist, he thought like one. He made a science out of looking at plants through different stages of growth as a way to understand the plant world and, in a broader sense, life.

In plant development, he figured out that everything was essentially leaf, everything. He proved by drawings and research that the leaf turns into the next stage of the plant and then the next, and the next. The flower is still a leaf.

Everything is still the same thing. And over the evolution of the plant world, it has moved into different forms.

Once I started getting information on his techniques, I got excited about using that discipline in drawing. What I love about this system is that you start from the source of a living thing. It could even be a stone. If you look at a stone and you want to draw it, that’s your source. You can treat it as living by giving it a history, thinking of its whole time of being.

I like to say, “I’ve known this plant since he was a seed.” That’s pretty much the beginning for any kind of object, a seed. I watch it every day until it reaches its final point, and then it begins to die. Then I’m thinking about what kind of elements were in that particular plant that are going to be broken down into compost for the next seed. From seed to seed again.

It’s like a saying that Paul Klee has, “Astonish me.” Unconsciously, I am asking for that.

The Garden as Studio

Let’s talk about the garden. Is the art inspired by the gardener? Is the garden planted to make the art? How do they work together?

It’s where it begins and where it ends. It is the cycle. For me, the garden isn’t separate from the studio; it’s part of the work. I don’t separate myself as a gardener from my art. They’re completely overlapping and necessary for each other’s being. One cannot exist without the other. Right now, as an artist, I need the garden. And the garden needs the art because the reason I’m making art is to expand the garden into a different material form. Sometimes the painting turns into a trip to the garden, and then to the kitchen, and then back to the canvas. The garden, kitchen, and studio are all beneficial. And it just flows.

Many people garden to control or maintain, but for me, the garden has its own life. When I was young, working on our family farm, everything was harvested and cleared. I never saw what came after.

Now, there are certain areas that we leave for the plants to complete their whole life cycle, from seed to the final giving-up of their form. Just to let them have their full life.

I have to say our garden because my sister Fern is very much equal. She is a partner with me in everything, and she’s taken to doing more since I’ve been more focused on my art.

Fern and Mare Martin

A Sanctuary for Weeds

Can you describe your “weed sanctuary”?

Oh, yes! There’s a part of our garden, a special place for weeds to grow. It’s sort of like a weed sanctuary. We fenced off the area and we made a place where be whatever they want to be and grow as long as they want. We’re not going to pull them up, and we’re not going to trim them. We’re not going to touch them.

Roots and Rhythm

How did growing up here, on this farm, and in this area shape your outlook?

I was born in South Louisiana of Cajun descent and spent most of my formative years on this farm.

We moved here when I was nine. It was a real working farm, with cows, chickens, horses, and gardens. I’d lived in the city before that, always cars going by, always activity. Here, suddenly, there was space and quiet. I lived in a magical world of animals, plants, and nature. It’s just this amazing, magical place.

You lived abroad for a while and traveled. Can you talk about the value of these different experiences?

Traveling is a deep experience, especially when you move away from a farm to a foreign country. Then you see such different things and you come back enriched.

I lived here from the time I was nine to the time I went to college.

Then I went to art school, moved to New Orleans, and raised my family. I had three children in two years. I was a mother for that whole time. I didn’t do anything else.

From New Orleans, we went to live on a farm as caretakers in southern Spain and stayed there a year. My husband painted, and I did botanical drawings.

We came back here, and I started making gardens again and opened up an herb nursery.

I would make these intricate drawings of the gardens at the site. My first garden was at the Cafe Vermilionville, and that started the whole line of gardens.

After the kids were in college, my husband and I rethought our lives and we moved to New Mexico, to a little town called Dixon. It was paradise, the land of enchantment! I stayed there twelve years. My husband and I separated, and then my dad got ill, so I came back to help take care of the family. It was after Katrina. I remember because everybody from Katrina was evacuating. Later, my sister and I built a studio and I started teaching classes.

But to be doing this right now is a high point in my life.

It’s like I have a mission and I’m feeling really good about where I am.

So, what is that mission?

My mission is to show people that connection—to nature, to attention—can be found anywhere. You don’t need a big studio or elaborate tools; just a pencil, a piece of paper, and a plant. You can find something right next door that can give you peace of mind or a reason to live.

It’s a way to love the world.

How does it feel to have an exhibition at the Hilliard?

I’m having an exhibit at the Hilliard Art Museum in Lafayette called Beyond the Botanical, covering two decades of my work. It’s a culmination. I’m just ecstatically happy about it and hope that it will mean something to people who come to see it.

Looking Forward

And what’s next for you?

Ha! I found a plant that called me so strongly. It’s in a park, growing through a wall where it shouldn’t be. After the exhibition, I am going to go back to the park, to that plant, and draw it, because it’s going to be a painting.

That’s what I’m going to do next.

Acknowledgments

Beyond the Botanical is Presented by Kiki Frayard

The Hilliard Art Museum extends heartfelt thanks to Mare Martin for sharing her time, her insight, and her way of seeing. Her reflections remind us that attention itself can be an art form—and that the natural world, in all its intelligence, continues to be our most enduring collaborator. Beyond the Botanical celebrates that same attentive spirit, inviting visitors to experience the dialogue between art and nature through Martin’s work.

Thank you to Fern Martin for co-hosting the team in Opelousas. Special thanks to Allison Bohl DeHart, ULL Alumni and MakeMade for their collaboration on this studio session video and photography.